Mediterranean

Christmas at the world's deadliest sea border

There is a long history of migration via the Mediterranean. Human mobility in all directions across the Mediterranean has occurred for thousands of years. More recently, since at least the mid-1990s, tens of thousands of people each year have crossed the Mediterranean by boat from the northern coasts of Africa and Turkey to seek asylum or to migrate to Europe.

The Central Mediterranean Sea is the deadliest border to Europe. In 2014 and 2015, about 320,000 people crossed the sea from North Africa to Europe, mainly to Italy and Malta. In 2015, the majority of sea entries to Europe went across the Eastern Mediterranean to Greece. However, the Central Mediterranean saw the highest number of deaths.

In 2023, at least 3.129 children, women, and men trying to cross into Europe were reported missing or dead at sea: an average of 8 victims per day. The deadliest year since 2017. While Libya remains the main country of departure, during 2023 departures from Tunisia have dramatically increased, more than doubling the 2022 figure. The vast majority of migrants have been smuggled by human traffickers, who in some cases charge thousands of euros to try to take migrants to the European mainland. Many suffer grave human rights abuses prior to embarking on their sea journeys – with no guarantees of ever making it across to Europe.

Since 2014, there have been about 30.000 confirmed deaths at sea, but the reality is that many people cross the sea or lose their lives trying without ever being found.

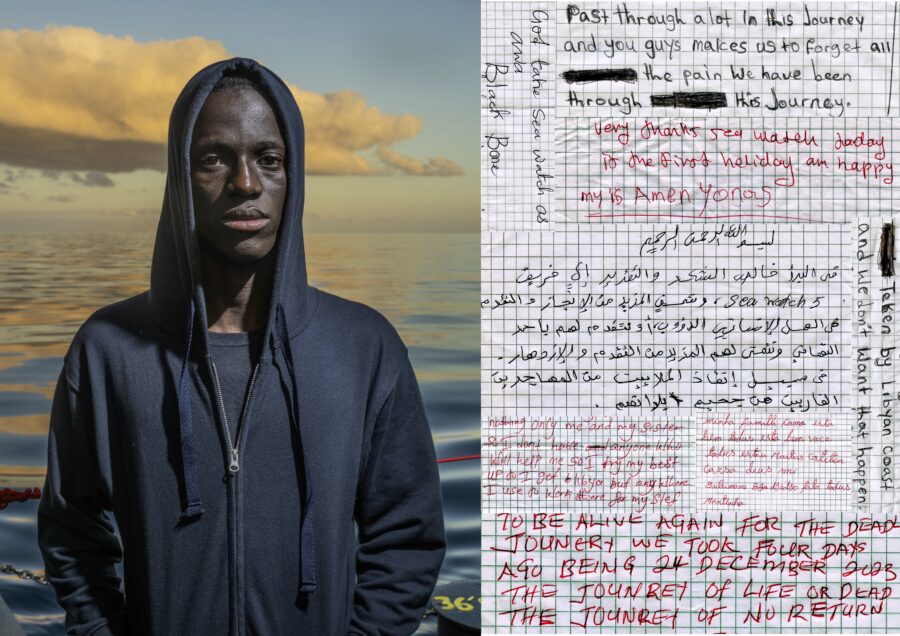

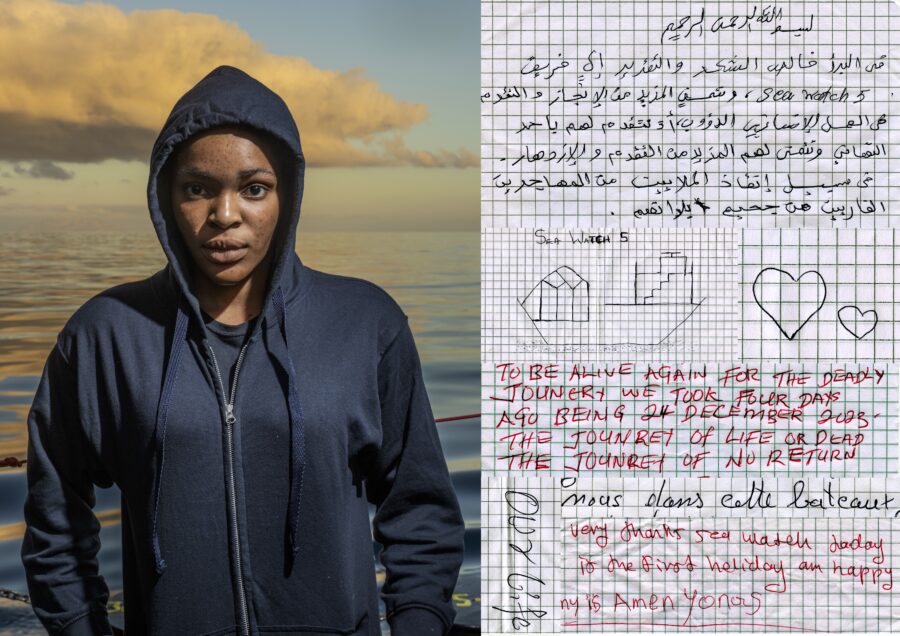

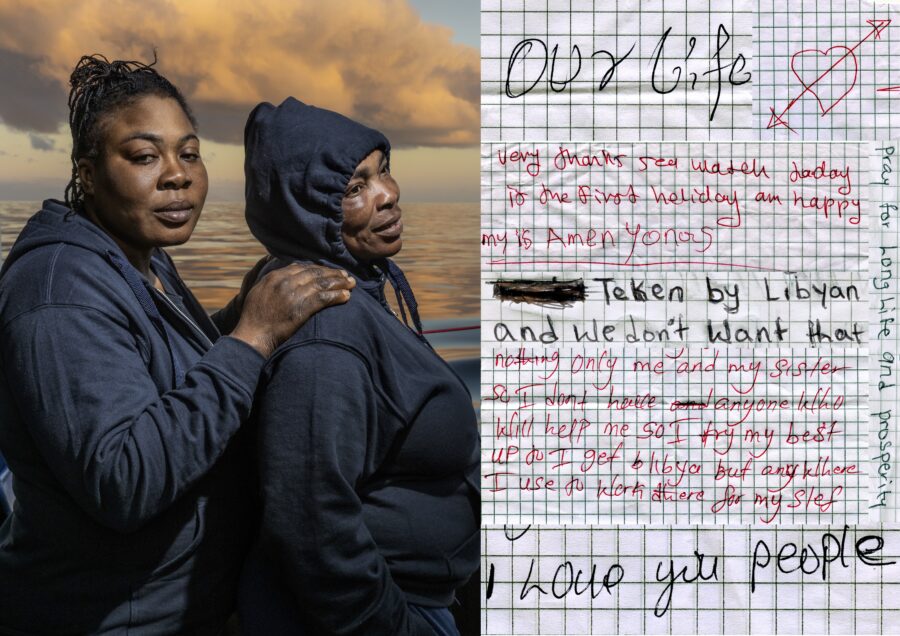

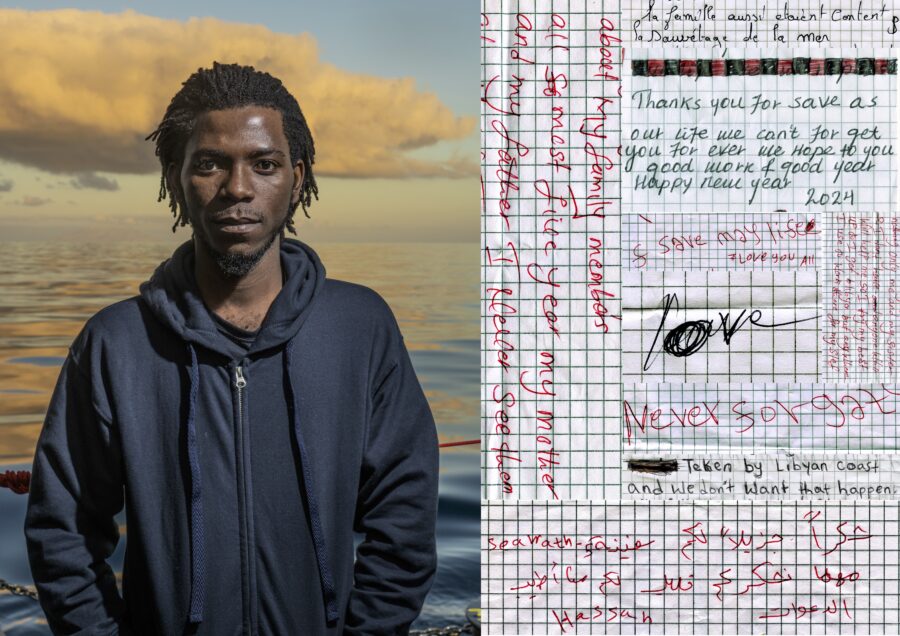

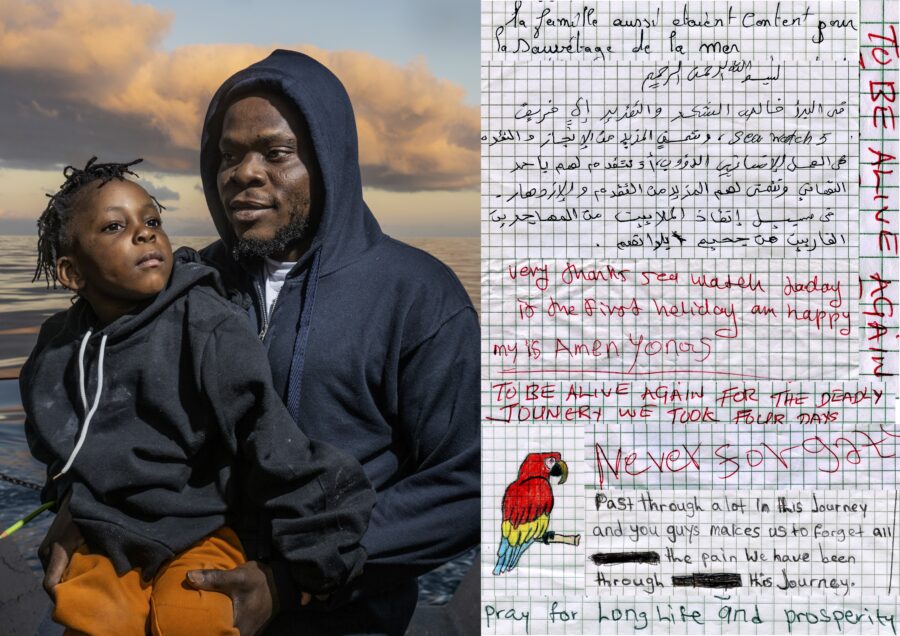

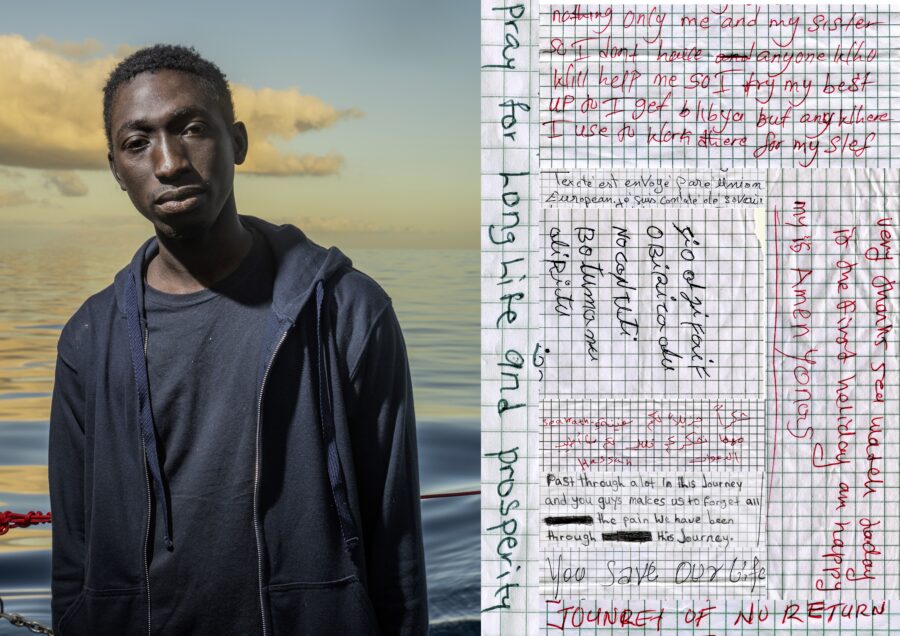

With humanitarian corridors not being an option for the vast majority of refugees detained or transiting in Libya or Tunisia, risking their lives at sea is the only way out the country. All survivors agree: in the places they fled from they endured continuous violations of their human rights. Working for no money, walking on the street and being kidnapped so ransom can be asked to families back home, violence, murders, forced eviction, destruction of property, detention, arbitrary arrests for the intention of leaving the country (even to go back to the country of origin): life for migrants is very hard in Libya and facing the sea is often the only viable way out.

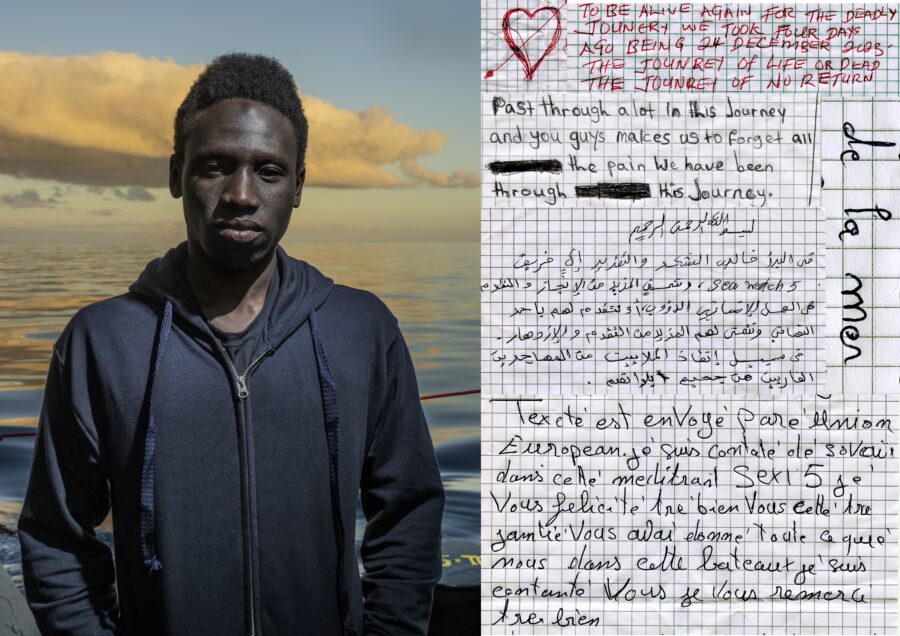

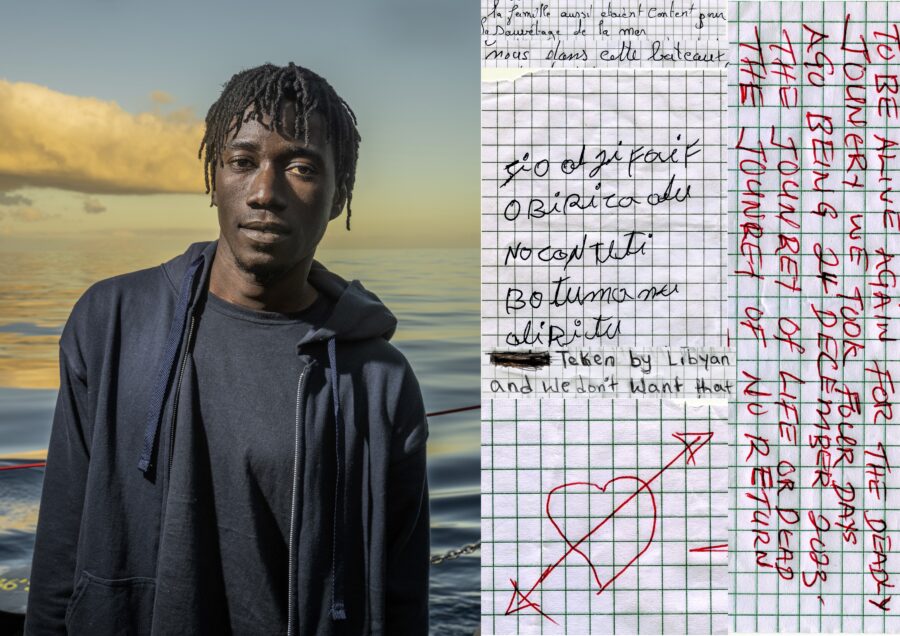

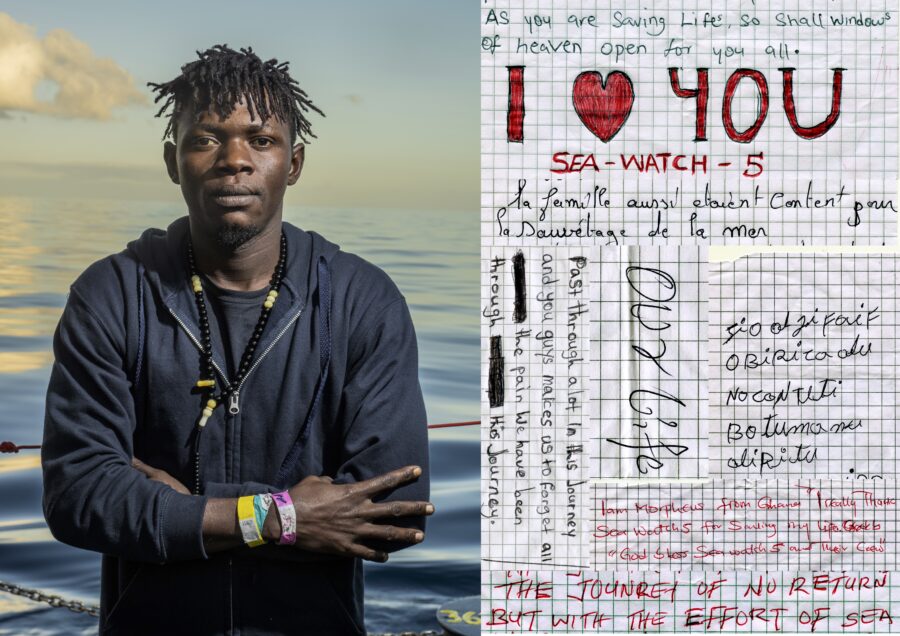

The crossing of the Mediterranean is just as unanimously described as a perilous ordeal, a ‘journey of life or death’ by the survivors, who are fully aware that they might lose their lives at sea but choose it over staying.

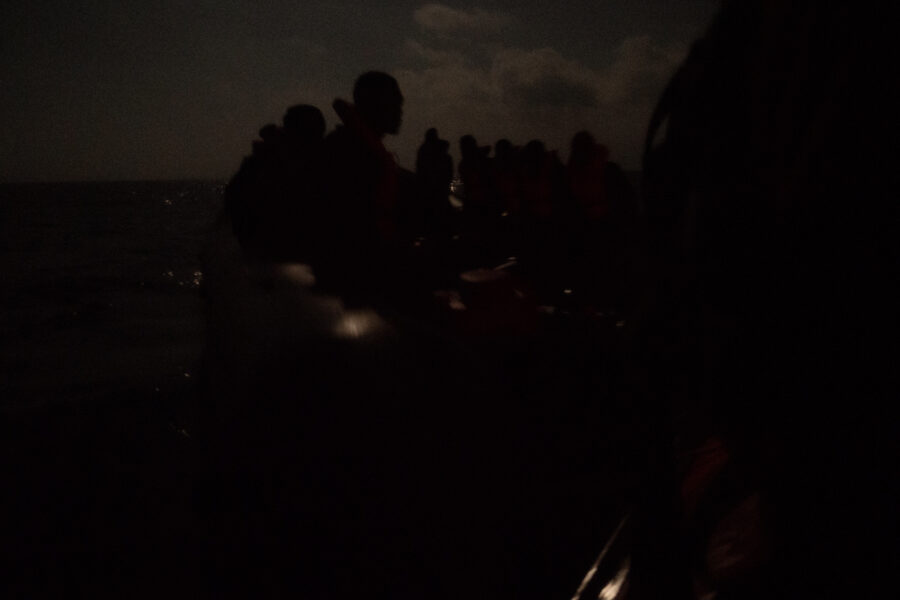

Unstable and overcrowded rubber, wooden or iron boats, no food nor water for days, deteriorated physical and mental health conditions, exhaustion, dehydration, extreme temperatures, inability to change position, tension, smell of fuel and fuel burns, no GPS nor satellite communication, sea sickness, waves, fear and hope; with a distance that varies between around 400 and 500 km to Italian and Maltese shores, the conditions of the journey are close to impossible.

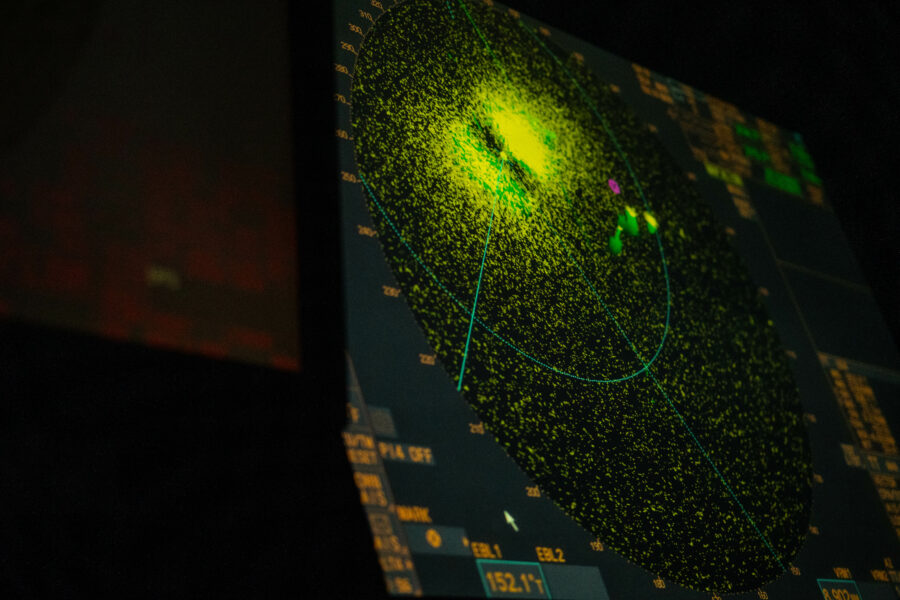

SOS calls are often bounced between competent authorities and result to be either ignored or acted upon after an exceptionally long wait, with shipwrecks potentially occurring before rescue is eventually underway.

Intercepted migrants often end up in dangerous situations and face serious human rights abuses at the hands of the Libyan state actors. Libya is not officially not considered safe for migrants and interceptions violate the fundamental human rights of fleeing and seeking asylum, however Libyan state actors are more and more supported, trained and financed by the European Union to prevent people from crossing the sea through deals that are not in line with international law. Only 5% of the migrants leaving the North African coasts reach Italian territories independently. The vast majority of those reaching the country are rescued by Italian authorities. Nevertheless, the work of non-profits has been proven to be essential in preventing more deaths at sea.

Non-governmental organizations carrying out search and rescue (SAR) operations have been a constant presence in the Mediterranean since 2014, seeking to fill the void left by the lack of state-organised SAR operations. The European Union and especially Italy are increasingly implementing stricter migration policies, essentially criminalizing NGOs carrying out SAR activities. The recent practice of assigning distant ports for disembarkation, for example, keeps rescue ships away for days from the search and rescue area in the central Mediterranean where most distress cases occur. NGOs continue their tireless search and rescue activities at sea.